Of all the sectors of the Italian front, the Karst Plateau and the

Isonzo river, roughly marking the border between the Kingdom of Italy and the

Austro-Hungarian Empire (nowadays, between Italy and Slovenia, where the river

is called Šoca), where the place where the bloodiest battles took place.

Between May 1915 and October 1917, the Italian army focused most of its

effort in this area; General Luigi Cadorna, the Italian Chief of Staff, hoped

to achieve a breakthrough on the Karst Plateau, where the terrain was

relatively less mountainous than in the rest of the Alpine front, and thus to

overflow through Slovenia towards the Hungarian plain. Had this succeeded, the

Italian Army would have cut in two the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and could

possibly marched towards Vienna as well.

This success, however, never materialized; the Italian forces, although

enjoying numerical superiority in both men and artillery, were still in a

unfavourable position and had to face determined foes whom strongly fortified

the many rocky hills and small mountains of this area, some of the most

infamous being Monte San Michele (276 m, 905 ft), Monte Santo di Gorizia/Sveta

Gora (681 m, 2,234 ft), Dosso Faiti/Fajtji hrib (432 m, 1,417 ft), Monte

Sabotino/Sabotin (609 m, 1,998 ft), Podgora (241 m, 790 ft), Monte San

Gabriele/Škabrijel (646 m, 2,119 ft), Monte Ermada/Grmada (323 m, 1059 ft).

Each of them became a fortified stronghold, for whose control thousands of men

killed each other; many of these positions were lost and recaptured several

times.

Similarly to the Western Front, attacking troops (Italians, in this

case) were repeatedly sent to slaughter against barbed wires, under heavy enemy

fire; advances of a few hundreds of meters were paid with the loss of tens of

thousands of men, mowed down by the machine guns. Austro-Hungarian troops, in

turn, suffered heavy losses caused by heavy artillery barrages. When attacking

troops reached the trenches, the assault turned to hand-to-hand combat were

bayonets, knives, swords and even scrap metal and debris were used. The first

gas attack on the Italian front happened there on 29 June 1916; a

Austro-Hungarian gas attack on Mount San Michele resulted in 2,700 Italians

killed and 3,800 intoxicated by a mixture of phosgene and chlorine.

According to some estimates, up to 1,000,000 men on both sides were

killed or mutilated in the battles of the Isonzo; an estimated 300,000 Italians

and 200,000 Austro-Hungarians, if not more, had lost their lives there.

Twelve battles were fought here, all but the last one being Italian

attacks:

- the First

Battle of the Isonzo (23 June-7 July 1915) saw the failure of the Italian

offensive; Italian forces made limited gains, capturing heights near

Plezzo/Bovec and the westernmost ridges of the Karst Plateau near Fogliano

Redipuglia/Foljan-Sredipolje and Monfalcone. More gains were made, but

soon lost to Austro-Hungarian counterattacks. Italian casualties were

14,947 men (including about 2,000 killed), Austro-Hungarian casualties

9,950 men (including about 1,000 killed).

- the Second

Battle of the Isonzo (18 July-3 August 1915) was an Italian victory, with

the conquest of Mount Batognica (2,164 m) and Mount Nero (2,245 m);

Italian forces also captured Mount San Michele, but lost it to

Austro-Hungarian counterattacks, maintaining however important strategic

positions (Bosco Cappuccio). The battle ended when both sides ran out of

ammunition. The Italians lost over 6,000 men killed, 30,000 wounded, 4,900

missing and prisoners; Austro-Hungarian losses were overall 46,600 men.

- the Third

Battle of the Isonzo (18 October-4 November 1915) was an Austro-Hungarian

victory; most gains made by Italian forces were lost to Austro-Hungarian

counterattacks. Italian casualties numbered 67,100 men, of whom 11,000 were

killed; Austro-Hungarian losses were 40,900 men, of whom 9,000 were

killed.

- the Forth

Battle of the Isonzo (10 November-2 December 1915) saw another

Austro-Hungarian victory, with most Italian attacks being repelled. The

town of Gorizia was almost entirely destroyed by Italian artillery.

Italian forces lost 49,500 men (including 7,500 killed), Austro-Hungarian

forces lost 32,100 (4,000 killed). The arrival of the winter, with caught

both belligerents unprepared, brought the battles to a stop for the following

months.

- the Fifth

Battle of the Isonzo (9-15 March 1916) was inconclusive; an Italian

offensive, launched under French pressure as a diversion of the battle of

Verdun on the Western Font, made little gains. This battle was less bloody

than the others that preceded and followed it; Italian and

Austro-Hungarian overall casualties were, respectively, 1,882 and 1,985

men.

- the Sixth

Battle of the Isonzo (6-17 Augst 1916) was an Italian victory, with the

conquest of Gorizia as well as several Karst heights (including Mount San

Michele). It was a costly victory, with 51,000 casualties on the Italian

sides (of whom 21,000 were killed) and 41,835 on the Austro-Hungarian side

(of whom 8,000 to 9,000 killed).

- the Seventh

Battle of the Isonzo (14-18 September 1916) was inconclusive; an Italian

attempt to enlarge the Gorizia bridgehead, by concentrating more resources

on a smaller sector of the front (oppositely to the previous battles,

which had seen broader attacks on larger parts of the front; it was also

hoped that this could reduce the grievous casualty rate sustained until

then), substantially failed, but at the same time the attack further

weakened the Austro-Hungarian army, both in manpower and artillery

availability, driving it closer and closer to collapse (unless Germany

would intervene). Italian casualties were between 17,500 and 21,144 men,

Austro-Hungarian losses were between 15,000 and 20,000 men.

- the Eighth

Battle of the Isonzo (10-12 October 1916) was basically a repetition of

the seventh battle, with only a few hundreds more meters captured by the

Italians. Within the space of three days, the Italians suffered 25,000

casualties, while the Austro-Hungarians lost between 25,000 and 40,000

men.

- the Ninth

Battle of the Isonzo (31 October-4 Novembre 1916) was the last Italian

offensive before winter, and was still similar to the previous two. The

Italian troops advanced of about five kilometers, capturing several

positions and hills including the infamous Dosso Faiti; this advance was

however very limited, and paid with the loss of 39,000 men.

Austro-Hungarian casualties consisted of 33,000 men.

- the Tenth

Battle of the Isonzo (10 May-8 June 1917) saw a return to attacks on large

parts of the front; Italian troops attacked on a 40-km front, aiming at a

breakthrough towards Trieste. By the end of May, the Italian troops had

advanced considerably, capturing a number of key positions and uplands and

the village of Jamiano, and advancing to within 15 km of Trieste; on 3

June, however, the Austro-Hungarians launched a major counteroffensive,

which recaptured nearly all lost ground. Farther north, between Monte

Santo and Zagora (north of Gorizia), Italian troops passed the Isonzo and

formed a bridgehead, but their conquest of Monte Santo was frustrated by a

Austro-Hungarian counterattack. This was one of the bloodiest battles

fought on the Isonzo front, with 160,000 Italian casualties (including 36,000

men killed) and 125,000 Austro-Hungarian casualties (including 17,000

killed).

- the

Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo (18 August-12 September 1917) was the most

massive attack launched by the Italian Army on the Isonzo front, with 600

battalions (supported by 5,200 guns) launched against 250 battalions

(supported by 2,200 guns). Italian troops captured Monte Santo and the

Bainsizza/Banjšice Plateau, whereas Monte San Gabriele was captured but

lost again and Mount Ermada was not captured. The Italians lost 160,000

men (30,000 killed, 110,000 wounded, 20,000 missing or captured), the

Austro-Hungarians lost 120,000 (20,000 killed, 50,000 wounded, 30,000

missing, 20,000 captured). The Austro-Hungarian Army was left on the brink

of collapse, unable to withstand another attack; but the Italian Army was

not really in better condition, and was thus unable to launch another

assault.

- the Twelfth

Battle of Isonzo, best known as the Battle of Caporetto, began on 24

October 1917. After repeated requests from Austria-Hungary, Germany sent

reinforcements, and a major Central Powers offensive was carefully

planned. With the decisive help of German assault troops, infiltration

tactics teached by them to the Austro-Hungarians, and the use of poison

gas, Central Powers forces broke the Italian lines at Caporetto, setting

off a retreat which soon became a tragic rout. In what has gone down in

history as the worst military disaster in Italian history, the

Austro-German troops invaded in less than a month all of Friuli and the

northern and eastern parts of Veneto, also causing the fall of the

Dolomite front and advancing within a few kilometers from Venice. Between

10,000 and 30,000 Italian soldiers were killed, 30,000 were wounded,

265,000 were captured (many of whom would die of illness or starvation in

captivity), 50,000 deserted, 300,000 were left temporarily scattered. The

Italian Second Army ceased to exist. 600,000 civilians from Friuli and

Veneto left their homes and joined the retreating troops, ending up in

refugee camps scattered throughout Italy.

When the war ended, dozens of small cemeteries littered the Karst

plateau and the Isonzo valley. The area of Redipuglia, on the Karst plateau,

had seen heavy fighting during the early battles of the Isonzo; it was decided

to build there the first great cemetery for the Italian soldiers killed on this

front. The first cemetery, designed by General Giuseppe Paolini and Colonel

Vincenzo Paladini, was completed in 1923; located on Colle Sant’Elia (St. Elias

Hill), it was the resting place for 30,000 Italian soldiers, either transferred

there from smaller cemeteries in the surrounding area, or recovered from the

battlefields.

By the early 1930s, however, this cemetery had deteriorated, and it was

decided to transfer the dead to a new, larger war memorial, that would also

“house” the remains of dozens thousands more men, initially buried in other

cemeteries.

The new Redipuglia War Memorial, designed by architect Giovanni Greppi

and sculptor Giannino Castiglioni, was built between 1935 and 1938. When it was

inaugurated, on 18 September 1938, more than 50,000 World War I veterans

attended the ceremony.

The shrine, built on the slopes of Mount Sei Busi, contains the remains

of 100,187 men. 72 of them belonged to the Navy, 56 to the Guardia di Finanza;

the others were all officers, NCOs and soldiers of the Army. This makes

Redipuglia the largest Italian war memorial, and one of the largest in Europe and in the world.

At the base of the war memorial there are the graves of five general of

the Third Army: Antonio Chinotto, commander of the 14th Division, who died of

the illness on 25 August 1916; Tommaso Monti, commander of the "Forlì"

Brigade, killed by grenade on Škabrijel on August 29, 1917; Fulvio Riccieri, commander

of the "Puglia" Brigade, killed in combat near Flondar (Karst) on June

4, 1917; Giuseppe Paolini and Giovanni Prelli, who died after the war. Next to

them is also the sarcophagus of Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy, Duke of Aosta,

commander of the Third Army for the entire duration of the war, who died in

1931 and wanted to be buried with his men. The figure of the Duke of Aosta, widely

praised and celebrated after the war and in the Fascist period, is actually

quite controversial; his conduct as commander was not very different from that

of Cadorna, with useless and bloody frontal assaults, summary executions and

decimation for "unruly" units. After the war, he was also one of the main

supporters of fascism in the House of Savoy.

The memorial is made of 22 "steps" in which are buried 39,857

identified dead, while on the last step are a votive chapel and two mass graves

containing the remains of 60,300 unidentified soldiers. On top of the memorial,

three large crosses symbolize the Golgotha.

In the midst of all these men also lie the remains of a woman, the only

one: Margherita Kaiser Parodi Orlando, 21, a Red Cross volunteer nurse. She worked

in hospitals immediately behind the front for four years, from 1915 to 1918, sometimes

even under artillery bombardment; after the end of the war, she continued to

work at the hospital in Trieste, where he died of Spanish flu on 1 December

1918.

At the foot of the shrine lie an armored trench dating back to the war,

where fighting took place in the first two battles of the Isonzo.

The Colle Sant'Elia, where the original cemetery once stood, has been

turned into a Park of Remembrance; along its boulevards one can see the remains

of trenches and caves dating back to the war, as well as more than thirty

artillery pieces, and 35 memorial stones with inscriptions dedicated to the

various corps and specialties of the Italian Army and objects of the "everyday"

life of the soldier, as well as stones that once were on the graves in the previous

cemetery. On top of the hill there is a Roman column coming from the

excavations of Aquileia.

The monument is completed by the "House of the 3rd Army," which

includes a museum on the Great War on the Karst plateau, primarily focused on

the events involging the Italian Third Army, to which belonged almost all the

fallen buried here.

THE MEMORIAL

|

| The grave of the duke of Aosta. |

|

| The graves of the generals. |

|

| "[Here lie] thirty thousand unknown soldiers." |

|

| "Here died Giovanni Rossi from Teramo, Sergeant of the 10th Company of the 1st Sapper Regiment of the Engineer Corps, on 2 July 1915. Gold Medal of Military Valor". |

|

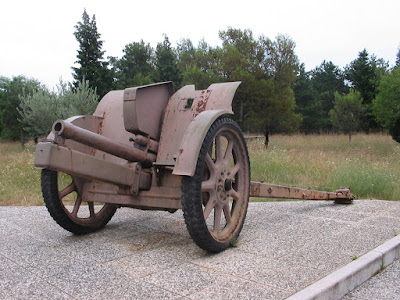

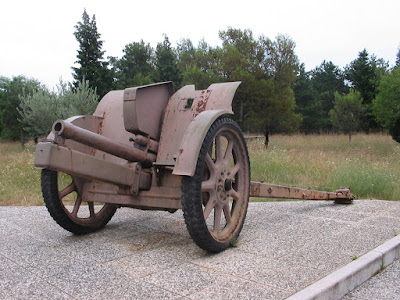

| Two 75/27 mm Mod. 1911 guns are also on top of the war memorial. |

|

| Aggiungi didascalia |

|

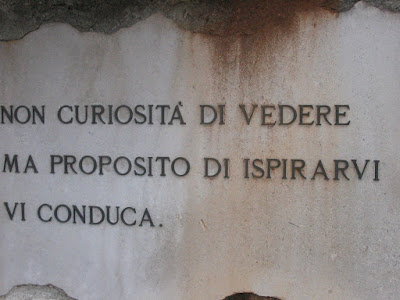

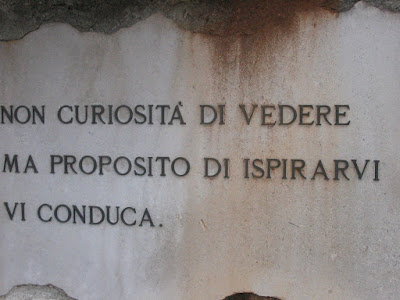

| "Don't let curiosity to see guide you, but rather purpose of inspiration". |

THE COVERED ("ARMOURED") TRENCH

|

| The trench was built and held by soldiers from the "Siena" Brigade (31st and 32nd Infantry Regiment) and later the "Savona" (15th and 16th Infantry Regiment) and "Cagliari" (63rd and 64th Infantry Regiment) during the first and second battle of the Isonzo, in June-July 1915. |

ST. ELIAS HILL (COLLE SANT'ELIA) - PARK OF REMEMBRANCE

|

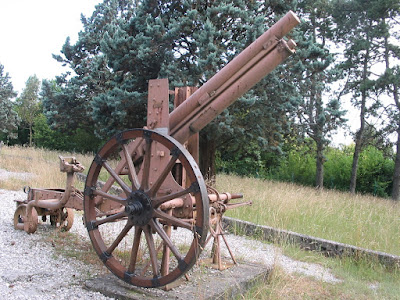

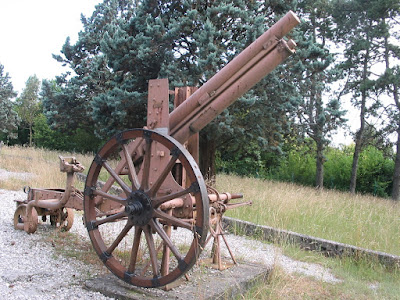

| German 170 mm mortar (17 cm mittlerer Minenwerfer). |

|

| Italian 149 mm steel gun ("149 A" or "149/35 Mod. 1901"), the most widely used Italian heavy gun in World War I. |

|

| This 149 A was manufactured in 1915 by Franco Tosi, Legnano (not far from where the author lives). |

|

| Austro-Hungarian 200 mm mortar ("20 cm Luftminenwerfer M.16 Spitz"). |

|

| Italian 149 mm cast iron gun ("149 G" or "149/23"), |

|

| "Cavalry - Soldiers of every war, hard with the bayonets, along with our infantrymen" |

|

| "Cyclist Bersaglieri - My wheel is toughed with courage in every spoke, and on the wheels stands the Fate, without blindfold". (The Italian text is rhymed). |

|

| "Seamen - Dead like on the deck of a ship, like seamen, they know how to die anywhere". |

|

| Trench with mortar position. |

|

| "Alpini - For us, infantrymen of the Karst, it is a privilege to sleep beside the pure heroes of the mountains, our Alpini brothers". (The Italian text is rhymed). |

|

| "Unknown soldier - Why do you care about my name? Shout to the wind "SOLDIER OF ITALY" and I will sleep satisfied". |

|

| "Wire cutters - If wire cutters were useless, teeth did the work." |

|

| "Guardia di Finanza - Italian or foreigner, do not smuggle goods against Italy" |

|

| "Trench club - New weapon for an ancient barbarity: the anger of the enemy unleashed everything on us". |

|

| Shelter in cave. |

|

| Austro-Hungarian 22.5 cm Bohler bombard. |

|

| "Marmite - A hit, a great crash - and for a day, the soldier only lived on faith" |

|

| "The Red Cross nurse - You were for us, amid bandages, the maid of charity - Death grabbed you among us. Stay with us, sister!" This epigraph was originally on the grave of Maria Kaiser Parodi Orlando. |

|

| "Captain Gerardo Bamonte of the 122nd Infantry Regiment - While leading his valiant soldiers to glory, he heroically died on Mount Sei Busi on 26 July 1915, preceding in this supreme sacrifice his brother Vincenzo, Lieutenant of the Engineers, who, imitating the heroism of his brother, he gave his young life for the country on 15 October 1918, on the Piave river, seeing the victory near". |

|

| Italian 75/27 mm gun Mod. 1911. One of the most widely used Italian field guns, many still survive to this day. |

|

| "The can - Full of wine one day, then red with blood, from the ravaged trench the can came back to us". (Italian text is rhymed). |

|

| "The medical officer - (Latin): To save the life of the brothers" (mott of the Italian Army Medical Corps). |

|

| Italian 152/13 mm howitzer (British-built, Ordnance BL 6 inch 26 cwt howitzer). |

|

| 152/13 mm howitzer. |

|

| Trench shelter. |

|

| Machine gun position in trench. |

|

| Shelter in gallery. Built by the Austro-Hungarians in spring 1915, completed by the Italians after they captured the hill. It was used again in World War II, during the German occupation (1943-1945), by Flak personnel. |

|

| Italian 149/12 mm howitzer. |

|

| "Unknown soldier - The grave cannot tell my name, but God knows and blesses it". (Italian text is rhymed). |

|

| Bohler 22.5 cm bombard. |

|

| "Unknown soldier - Wind of the Karst, you, who know my name, kiss my mother on her white hair". (Italian text is rhymed) |

|

| Italian 105/28 mm gun. |

|

| Trench stove - I forgive you, who filled me with acrid smoke in the terrible days of Bora! Now I don't need you anymore, since I warm myself up besides the sacred flames of Italy". (Italian text is rhymed). |

|

| "On the grave of an unknown soldier: Take off your hat: I am duty!" |

|

| "Ghirba [a kind of wineskin used to carry water in Arab countries, "discovered" by the Italian Army during the Italo-Turkish War; it also meant, in military jargon, one's life - "salvare la ghirba" meaning "save [one's] skin"], your name surely sounds ironic to me: you saved yours, I did not save mine. (Italian text was rhymed). |

|

| A boat used by Engineers (Genio Pontieri) to build pontoon bridges. |

|

| "The shielded trench - More than the steel, the bare strong chest of the humble soldier was a shield to the trench" (Italian text is rhymed). |

|

| "The cannon - Once your shout and my roar - today, over us, the high voice of God" (Italian text is rhymed). |

|

| Austro-Hungarian 149/13 mm field howitzer (15 cm schwere Feldhaubitze M.14/16). |

|

| Naval 100/47 mm gun. |

|

Pontoon corps (Engineers) - And unto him the Duke: "Vex thee not, Charon;

my soldiers go other way to another shore; and farther question not" (based on a passage of Dante Alighier's Divine Comedy, Inferno, Canto III) |

|

| "The mess tin - My loyal mess tin, peace for you as well, now, over here: now I do not complain anymore if you are not full". |

|

| Austro-Hungarian 80 mm gun (M. 5/32). |

|

| "The pipe - My loyal friend in the bare trench" |

|

| "Machine gunners - ...the furious voice of the machine gun, terrible tree frog, who sings, never satisfied, in the storms of fire" |

|

| Italian 105/28 mm gun. |

|

| Naval 100/47 mm gun. |

|

| "Field telephone - Hello, who's calling? Yes, Dolina Amalia, Cima Tre is taken. Long live Italy!" (Italian text is rhymed) |

|

| 100/17 mm howitzer. |

|

| "The military chaplain - Soldier of the sword and of the Cross, I watch even in sleep. Listen to the voice. I speak to God, who charms the hearts. I say "Lord!" and you reply "Italy!". |

|

| Italian 75/27 mm gun. |

|

| "Aviators - Now only the wings of my dream still flutter". |

|

| Austrian 75/13 mm howitzer. |

|

| "Carabinieri - Guardians of the king and of the laws, only servants of duty, used to obey silently and to silently die, bane of the culprits, humble unknown heroes, obscure and great victims" |

|

| Bohler 22.5 cm bombard. |

|

| "Unknown officer - The humble soldiers knew my name when we jumped together shouting: Forward!" |

|

| "Barbed wire - these wires are not colored by rust: they are still red with our blood" |

|

| The Roman column from Aquileia on top of the hill. |

|

| The boulevard. |

|

| "Radiotelegraphy - Our entire history passed on these antennas, from the day of revival to the day of victory" |

|

| Italian 149/12 mm howitzer. |

|

| Austro-Hungarian 100/17 mm field howitzer (10 cm Feldhaubitze M16). |

|

| German 250 mm mortar (25 cm schwerer Minenwerfer). |

|

| Italian 105/28 mm gun. |

|

| "Officer Cadet Marinelli Luigi, 216th Infantry Regiment, 5th Company - Todi, Perugia, 1898 - Dosso Faiti, 1917." |

|

| A pile of gravestones from the previous cemetery. |

|

| "You who travel on the sacred roads of Italy, stop here, and, closed in the depth of your heart, climb St. Elias Hill as a devout offer of love and gratitude to the iron legionaries of the undefeated Third Army, that on the barren Karst colored in red the road to the long desided Trieste. Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia, Duke of Aosta." |

|

| "Colle di Sant'Elia (St. Elias Hill) - It was conquered after heavy losses by the valiant soldiers of the 17th Infantry Regiment ("Acqui" Brigade) on the attack of 9 June 1915. It was subsequently held by the soldiers of the "Siena" Brigade (31st and 32nd Infanty Regiment). From 1920 to 1938 it held the glorious remains of 30,000 fallen of the Third Army ("Cemetery of the Unbeaten"). |

|

| Another pile of gravestones. |

THE MUSEUM

More 75/27 mm guns.

|

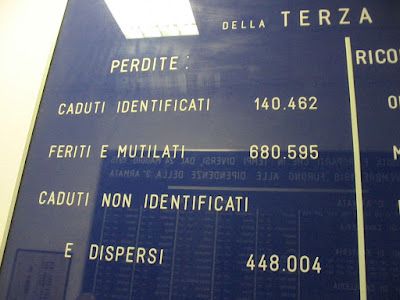

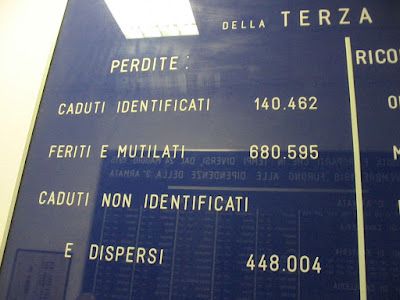

| A plaque summarizing the losses of the Third Army: 140,462 men killed in action; 680,595 wounded and mutilated; 448,004 unidentified dead and missing in action (prisoners included). |

|

| Machine guns - The one on the right is an Italian Revelli Mod. 1914 machine gun, 6,5 mm caliber. |

|

| Reconstructed machine gun post. |

|

| Reconstructed Karst terrain during the war. |

|

| Reconstucted barbed wire. |

|

| Rifles. |

|

| Gun and howitzer shells. |

|

| Reconstructed trench. |